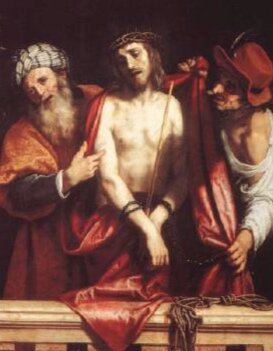

“Here is the man!” said Pilate.

“Idou ho anthropos!” said Pilate, in Greek.

“Ecce homo!” said Pilate, in Latin.

Man, anthropos, homo: this is the Human One.

We have four portraits of Jesus in our holy book. (Five, if you count Paul’s unique perspective.) John, unlike Mark, Matthew, and Luke, does something unique with the trial of Jesus: all four tell us that Jesus was flogged and mocked, but only John places this trauma in the middle of the trial.

And here is what happens when John tells the story in this way. Jesus is presented in a purple robe, the color of royalty, but the robe is placed on Jesus not to honor him, but to mock him, to make him look foolish. Then the highest-ranking government official in the region announces to the religious and political leaders that this is “the man.” Not the “King of the Jews,” not “one of the criminals I have in custody,” not “someone I think is innocent,” no, Jesus is “the man.” That is to say, in the expansive, inclusive language of our own time, Jesus is the Human One. Jesus is humanity. The leaders aren’t rejecting a defendant in a criminal trial in an ancient imperial backwater; they are rejecting the whole human race. Notice the present tense. They do it now as they did it then. They do it in this room. We do it. I do it. You do it.

Their condemnation is inhumane. It is an act of violence against humanity itself. God made us lovingly and proclaimed us very good, so all the terrible things we do to ourselves and one another are truly inhumane.

Inhumanity is so common, it is a literary motif. My tenth-grade American Literature teacher, Beverly Ekholm, taught me this. Mrs. Ekholm drilled it into us: “Man’s inhumanity to man,” she told us. That’s a motif found everywhere in literature.

Why?

Why are we so unkind to each other? Why, when confronted with an innocent person who has done nothing wrong, and already has been abused and jeered at and humiliated, why do we cry out for more, more abuse, more violence, another innocent death?

Why?

We are inhumane in all the massive ways. You know about these. The great historical atrocities: the slaughter of millions of Jews, which happened after centuries of misreading tonight’s Passion narrative and blaming the death of Jesus on the Jews, even though Jesus of Nazareth was a Jew, as were all of his followers, including Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who (John tells us) bury him royally, weighed down with a hundred pounds (!) of fragrant oils, a fabulously grand burial. Even if this is John masterfully using hyperbole to deepen the symbolism of the reign of Christ on the cross, it still reveals the inhumanity of anti-Jewish behaviors: that is not what Christ teaches us. That is not supposed to be who we are.

But there are genocides more recent than the Holocaust, genocides happening now. And there are the effects of genocides from further back, genocides that continue to be felt centuries later, like the genocidal treatment of indigenous peoples on this continent. There is slavery and the legacy of slavery, another centuries-long atrocity that weighs heavily on our national conscience, and on the political and economic injustices of today. There is unchecked climate change, a calamity that threatens millions of lives, and not just human ones.

“Why are the nations in an uproar?” cries the psalmist, uncounted centuries ago. “Why do the peoples mutter empty threats? Why do the kings of the earth rise up in revolt, and the princes plot together, against the LORD and against the LORD’s anointed? “Let us break their yoke,” they say; “let us cast off their bonds from us.”

Why?

And then there are the comparatively smaller atrocities. Shootings in elementary schools and high schools and universities and churches and night clubs and concert venues and movie theaters. The need for a #metoo movement to raise awareness about violence against women, a century after women’s suffrage. Domestic violence, seemingly on the rise, but probably just more visible now, because it’s slightly easier to report it.

And then there is all the everyday awfulness that I do, that we all do. Seeing the worst in people, gossiping, backbiting, belittling, one-upping. Microaggressions. Peter slicing off an ear in a desperate attempt to get back at the soldiers.

Why are we so unkind to each other?

Lesslie Newbigin was a theologian who looked for all of this awfulness, all of this “man’s inhumanity to man,” and found it at the foot of the Cross. “[T]his world which God made and loves,” Newbigin wrote, “[is] in a state of alienation, rejection, and rebellion against [God]. Calvary is the central unveiling of the infinite love of God and at the same time the unmasking of the dark horror of sin … the amazing grace of God and the appalling sin of the world.”

“Amazing grace,” and “appalling sin.”

“Here is the man!” said Pilate.

“Idou ho anthropos!” said Pilate.

“Ecce homo!” said Pilate.

This is the Human One.

And now hear this Good News. The people who condemned Jesus, the people you and I often join in our words and actions that damage humanity: they are not alone in looking upon the Human One, and making a judgment about humanity. A little while ago in this service, we prayed this prayer: “Almighty God, we pray you graciously to behold this your family, for whom our Lord Jesus Christ was willing to be betrayed, and given into the hands of sinners, and to suffer death upon the cross…”

That’s right, we prayed to God that God also might “behold the Man.” Look upon the Human One, we asked God. Look upon us, but do so graciously, we pleaded. And so God has. The Cross, we sing tonight, “towers o’er the wrecks of time.” It is that terrible crossing of amazing grace and appalling sin. It is that horrible intersection of the “wrecks” of human history and the resurrecting power of God. God looks upon the Human One and sees clearly everything, everything done and everything left undone. Every terrible thought in every broken heart. Every wound, both physical and spiritual, inflicted on every human person.

And God raises the Human One to life. God brings life from death. God beholds humanity, and God shatters the tomb we have constructed for ourselves.

On this, and on this alone, we place all our deepest hopes this night.

***

Preached on Good Friday, April 19, 2019, at Immanuel Church-on-the-Hill, Alexandria, VA.

Works cited or consulted:

Raymond E. Brown, A Crucified Christ in Holy Week (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1986).

Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989), 175.

Image:

Ecce Homo, by Lodovico Cardi (Cigoli), 1607.