In 1986, at the age of 16, I was a busboy and a dishwasher at a steakhouse in the village of Mendota, Minnesota. I still remember the radio blaring in the restaurant kitchen, with songs like “I’m Walking on Sunshine” by Katrina and the Waves.

Since then, in Episcopal churches, I’ve continued to work as a busboy and a dishwasher, many, many times.

For almost ten years I worked in various churches as a deacon, and now as a priest I still do diaconal things. And deacons are busboys and dishwashers in the Eucharistic life of the Church: deacons set the Table, and clear it. They help the other leaders clean up. Service is the essence of the deacon’s vocation. Service is also one of the four values we at Grace proudly put on our signs, our website, and our stationery: service, or diakonia, is a powerful part of who we are, here in this place. In all this we are imitating Jesus, who washed the feet of his friends.

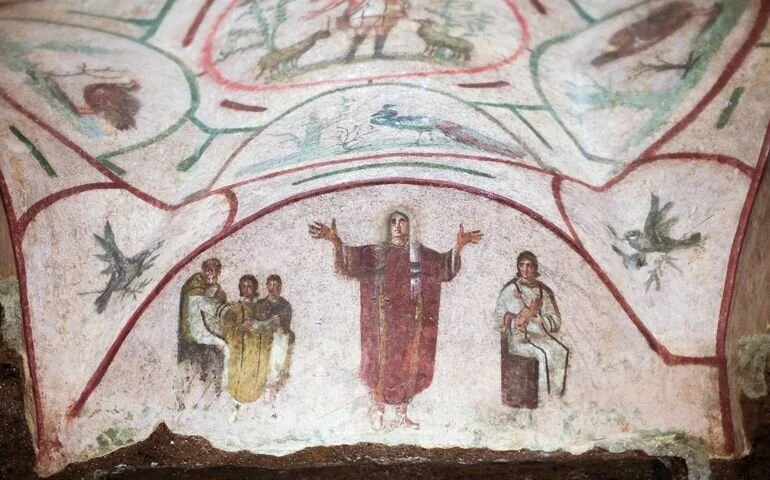

And now that we are once more celebrating Eucharist twice in person on Sundays, alleluia, I can’t help but think back to all those years I lived and worked as a deacon, setting and clearing the Eucharistic Table. I always stood a few inches back and to the side as the priest raised her arms in the ancient orans position, the posture of prayer shared by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike, the posture that resembles a large chalice, in which we pour all the intercessions and thanksgivings of our hearts, swirling together in prayer. We pour our prayers into that chalice, where they are mixed with God’s blessings, God’s power, God’s grace. In some traditions the deacon holds the actual chalice aloft as the Eucharistic Prayer concludes, bringing all the symbols together: all of us intercede with God for the whole world as God’s servants.

As a deacon, a servant, a busboy, standing a bit back and to the right of the priest, their arms raised in the orans position, I was occasionally conscious of the fact that I was standing directly behind the right wrists and hands of countless priests. Sometimes the light would glint off an elegant bracelet or wristwatch; sometimes the priest’s wrist was marked with a Jerusalem cross, evidence that they had been to the Holy Land and visited that tattoo shop in the Old City, so beloved of pilgrims. Sometimes I would notice, with admiration, a particularly good manicure. And if I was particularly attentive on a certain day, I might sense, or at least imagine, the emotional and spiritual burdens carried by that hand, the marks of grievous love from that time in the middle of the night when the priest used that hand to check his daughter’s temperature, or from that hard afternoon in the hospital when she extended that hand to touch the hand of a dying parishioner, in quiet vigil.

(Other times, I should put in here, I did my job properly and paid attention to the prayers we were all saying.)

But there was something prayerful about my preoccupation with wrists and hands, particularly the hands of priests, who usually were over me on the org chart. When I pray Psalm 123, our psalm this morning, my first instinct is to take the metaphor literally: I am a deacon looking to the actual hand of my supervisor. I am in a servant role, and I look over to see my boss, to take my cues from her, to have things at the ready in case she needs them, to respond to anything that comes our way. I am here to help.

But Psalm 123 says more with this image. (And no, it is not only about priests and deacons.) (And no, priests are not our masters!) In Psalm 123, we do not only look to God’s hand for guidance or orders; we look to God’s hand for something more. The psalmist sings that we look to God’s hand for mercy. Mercy, חָנֵּ֣נוּ, chanenu, a Hebrew word that means pardon, acquittal, I am free to go.

So, to build back from my first image today, of the deacon looking to the hand of the priest: The servant (deacon, priest, bishop, layperson, we are all servants!) - the servant looks to God’s hand, not for marching orders, and certainly not for punishment, let alone abuse. The servant looks to God’s hand for mercy. I look to God for freedom, for acquittal, for the good word that all is well, that I am restored, that I am okay, no, more than okay: I am good, I am forgiven, I am free. And, as usual in our spiritual life, we do this together.

Ezekiel is sent to the people of Israel to proclaim to them this mercy. Jesus sends his disciples on a similar errand, to go from village to village with the Good News of God’s free pardon, God’s intention to open God’s hand with mercy, not rejection.

And now I will ask what I often ask when we encounter the Good News: I invite you to wonder, where do you find yourself in the story?

Are you the prophet or disciple who is sent to proclaim God’s mercy to others?

Or are you the one in the village to whom those messengers of God are sent?

I have spent enough time in churches, working as a busboy, sure, but also preaching and teaching, heading up projects, and all the things, that I am formed to automatically see myself as the prophet or the disciple, the one being sent. And all of us have probably heard plenty of sermons that stay in that place, centering us as the ones being sent. That’s not wrong: we are supposed to be sent from here to share with other people the Good News, and, when necessary, use words.

But this time, I invite us to wonder about whether we are the ones to whom the messengers of God are sent. God’s messengers are being sent to us. If so, then —

Perhaps we look to God’s hand for freedom. We want freedom from our confining thoughts and feelings, freedom from the dull fever of our hungry hankerings, freedom from sadness over joys departed or loves lost, freedom from the old and sad divisions and misunderstandings that have torn and tattered our relationships. We want freedom from our old ways, our old assumptions, our old little prisons and jails.

Or, speaking of jails, perhaps we look to God’s hand for pardon. We want to settle an account that has us in arrears — as the Marvel Comics Avenger Natasha Romanoff says so well, we have “red on our ledger” and we want to fix that. Or we want forgiveness of an old mistake that continues to draw energy from us, energy that is lost or wasted, draining the power or the life force from everyone who was involved in that hard, sad story. Maybe we look to God’s hand to clean all that up, for and with us.

So we look to God’s hand. And “we” is all of us: priests and deacons and lay leaders, skeptics and outsiders, people in person and people online, newcomers and long-timers, children and youth and elders, all of us. We cast all our hopes and prayers into the chalice, and wait for God’s mercy to flow through them and change them into the festival drink that will gladden this feast.

And so, maybe, finally, it makes sense, in a backwards way, and is even appropriate that in these early days of re-opening, we still cannot drink together from the chalice! There is still a little bit of Advent, a little bit of waiting, of “now and not yet,” in our shared meal together, joyful as it already is.

God is here, and God opens wide God’s hand, with redemption and release.

But we still look to God’s hand. We still long to drink from the chalice. We still wait. There is still so much more to come.

I will close with a verse from an old hymn, a verse I have committed to memory because I think it may be one of the most heartfelt prayers I ever say, often enough while bussing this Table alongside you as your sibling and co-worker in God’s Church. This is one of the prayers I say, and sing, while I look to God’s hand:

I ask no dream, no prophet ecstasy,

no sudden rending of the veil of clay,

no angel visitant, no opening skies;

but take the dimness of my soul away.

***

Preached on the Sixth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 9B), July 4, 2021, at Grace Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, Washington.

Ezekiel 2:1-5

Psalm 123

2 Corinthians 12:2-10

Mark 6:1-13

Art: A priest holds her hands in the orans position, Catacombs of Priscilla, Rome.

Hymn stanza: George Croly, 1854.